The Mouse-Free Marion Project

Marion Island (29 000 hectares) and Prince Edward (4500 hectares), collectively known as the Prince Edward Islands (PEIs) were annexed by South Africa in December 1947 and January 1948, respectively. Since then, South Africa has maintained a research and weather station on Marion Island, Prince Edward remains uninhabited. The PEIs were declared a Special Nature Reserve in 1995, a Ramsar Wetland Site of International Importance in 2007 and the surrounding waters a Marine Protected Area in 2009. The islands, governed by a suite of national environmental legislation under the Prince Edward Islands Management Plan (which includes a plan for the control and eradication of invasive alien species), are managed by the Oceans and Coasts Branch of the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE) as the designated Management Authority under the National Environmental Management Protected Areas Act 57 of 2003.

Marion Island (29 000 hectares) and Prince Edward (4500 hectares), collectively known as the Prince Edward Islands (PEIs) were annexed by South Africa in December 1947 and January 1948, respectively. Since then, South Africa has maintained a research and weather station on Marion Island, Prince Edward remains uninhabited. The PEIs were declared a Special Nature Reserve in 1995, a Ramsar Wetland Site of International Importance in 2007 and the surrounding waters a Marine Protected Area in 2009. The islands, governed by a suite of national environmental legislation under the Prince Edward Islands Management Plan (which includes a plan for the control and eradication of invasive alien species), are managed by the Oceans and Coasts Branch of the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE) as the designated Management Authority under the National Environmental Management Protected Areas Act 57 of 2003.

The House Mouse Mus musculus (Photo Credit: Stefan Schoombie), inadvertently introduced to Marion Island by sealers in the early 1800s, successfully established on the island. With the human occupation of the island in 1948, four cats were brought to the island to control the mice in and around the station. However, these cats bred on the island, with their offspring becoming feral, and by the 1970s the population had increased to about 2000 individuals that were killing some 450 000 birds per year, mostly chicks of burrow-nesting species.

The House Mouse Mus musculus (Photo Credit: Stefan Schoombie), inadvertently introduced to Marion Island by sealers in the early 1800s, successfully established on the island. With the human occupation of the island in 1948, four cats were brought to the island to control the mice in and around the station. However, these cats bred on the island, with their offspring becoming feral, and by the 1970s the population had increased to about 2000 individuals that were killing some 450 000 birds per year, mostly chicks of burrow-nesting species.

With South Africa’s successful eradication of the cats in 1991 (confirmed in 1992), until recently the largest island upon which this has been achieved, the mice continued to thrive and over the years have had devastating effects on Marion’s fragile ecosystem by negatively affecting invertebrate densities, impacting on the vegetation by consuming seed loads and preying upon the chicks of burrowing petrels (since the 1980s) and surface-breeding albatrosses (since 2003), with ‘scalpings’ occurring from 2009 and attacks on adult birds recorded more recently in 2019. (Image Credit: FitzPatrick Institute)

With South Africa’s successful eradication of the cats in 1991 (confirmed in 1992), until recently the largest island upon which this has been achieved, the mice continued to thrive and over the years have had devastating effects on Marion’s fragile ecosystem by negatively affecting invertebrate densities, impacting on the vegetation by consuming seed loads and preying upon the chicks of burrowing petrels (since the 1980s) and surface-breeding albatrosses (since 2003), with ‘scalpings’ occurring from 2009 and attacks on adult birds recorded more recently in 2019. (Image Credit: FitzPatrick Institute)

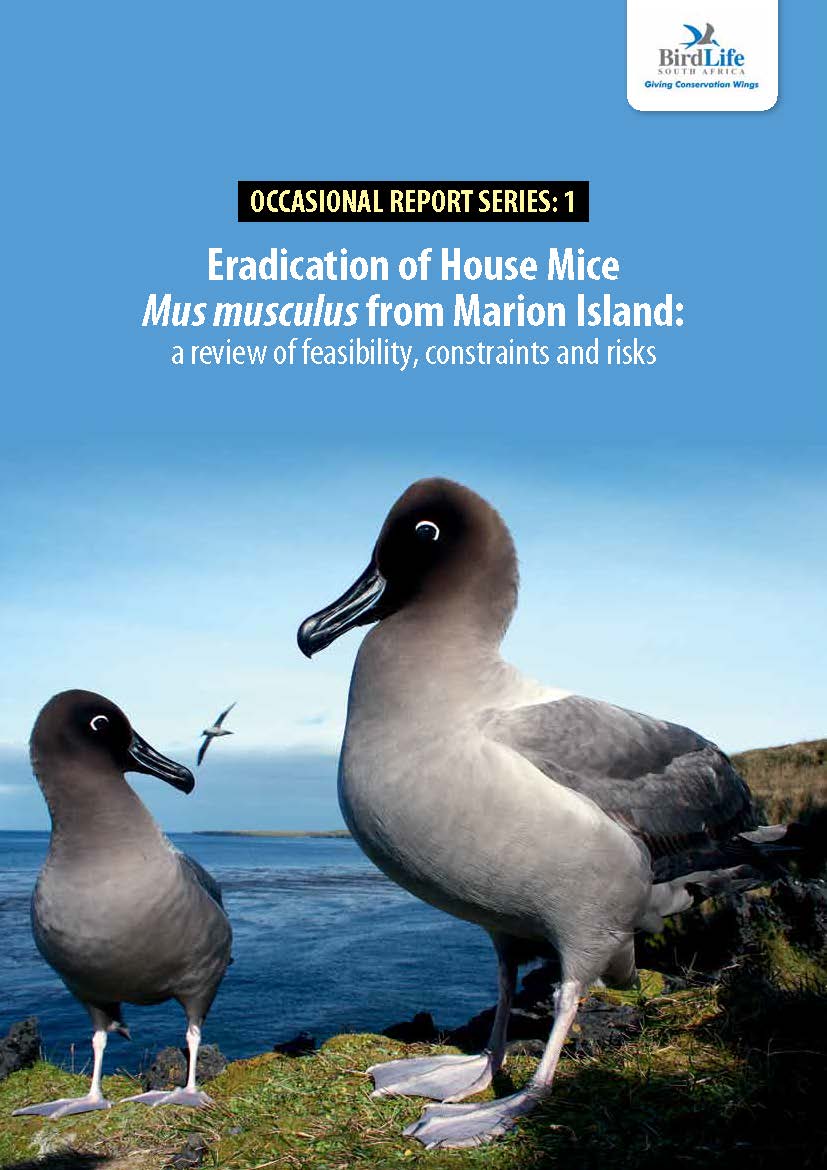

Marion Island supports some 25% of the world’s breeding population of Wandering Diomedea exulans, 12% of Sooty Phoebetria fusca and 7% of Grey-headed Thalassarche chrysostoma Albatrosses and smaller percentages of Light-mantled Albatrosses P. palpebrata and Grey Petrels Procellaria cinerea. It is clear something needs to be done or the severe impact of the mice could result in critical impacts on global populations and in the extirpation of up to 18 of the 27 bird species found on Marion within the next 30 to 100 years. (below l-r: Wandering Albatross, Sooty Albatross and chick, Grey-headed Albatross and chick. (Photo Credit: Stefan Schoombie)

In what would later become a partnership with DFFE, a Feasibility Study and Risk Assessment, undertaken in 2016 by John Parkes on behalf of BirdLife South Africa (BLSA), indicated that eradication was indeed possible. Also funded by BLSA, Draft Project and Operational Plans to eradicate mice on Marion Island were subsequently developed in 2018 by New Zealand eradication expert, Keith Springer, following an island visit. DFFE has been working closely with the UK’s Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) over the last few years in support of the Gough Island Restoration Programme (GIRP) which aims to eradicate House Mice on Gough during June to September 2021. For more information and the latest updates on the GIRP, please visit: https://www.goughisland.com

In what would later become a partnership with DFFE, a Feasibility Study and Risk Assessment, undertaken in 2016 by John Parkes on behalf of BirdLife South Africa (BLSA), indicated that eradication was indeed possible. Also funded by BLSA, Draft Project and Operational Plans to eradicate mice on Marion Island were subsequently developed in 2018 by New Zealand eradication expert, Keith Springer, following an island visit. DFFE has been working closely with the UK’s Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) over the last few years in support of the Gough Island Restoration Programme (GIRP) which aims to eradicate House Mice on Gough during June to September 2021. For more information and the latest updates on the GIRP, please visit: https://www.goughisland.com

On 12 May 2020, a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for the Mouse-Free Marion (MFM) Project was signed between DFFE and BLSA. Subsequently, a MFM Management Committee was established to initiate the development of the project and the two MoU partners are now working closely, together with various experts and institutions (including those involved with successful operations on other islands), on the detailed planning on all operational aspects required for the execution of this complex and costly project.

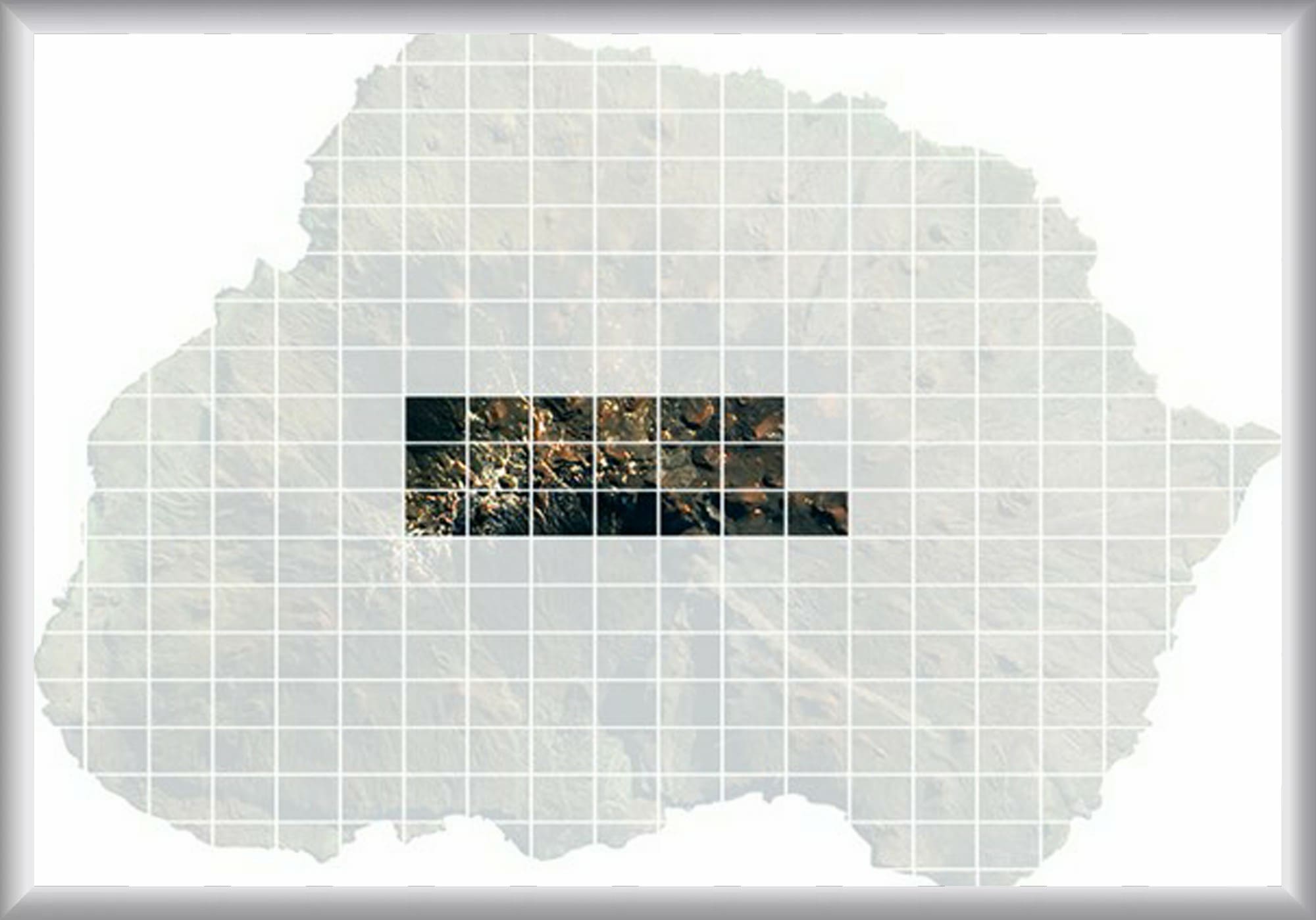

The MFM Project will make use of internationally agreed best-practice approaches to eradicate mice from the island. The Feasibility Study and draft Project and Operational Plans highlight that the only methodology offering any chance of success on an island of the size and topography of Marion Island is aerial spreading of bait containing a rodenticide with a proven capacity to eradicate mice.  The systematic aerial sowing of bait will be conducted by GPS-guided helicopters with underslung bait buckets to ensure every single mouse territory is covered. The aerial baiting will be complemented by hand-baiting approaches in and around the base and other infrastructure on the island. If a single pregnant female is not targeted, it could result in the failure of the entire operation, but if it works, Marion Island will be by far the largest island in the world from which House Mice have successfully been eradicated.

The systematic aerial sowing of bait will be conducted by GPS-guided helicopters with underslung bait buckets to ensure every single mouse territory is covered. The aerial baiting will be complemented by hand-baiting approaches in and around the base and other infrastructure on the island. If a single pregnant female is not targeted, it could result in the failure of the entire operation, but if it works, Marion Island will be by far the largest island in the world from which House Mice have successfully been eradicated.

Time window trade-offs have been assessed and it has been determined that winter (April/May – August/September) is the optimal period in which to implement an eradication operation. This is the non-breeding period for mice at Marion, when their population size is low and natural food resources are minimal, rendering bait more attractive. A winter-baiting operation also reduces the risks to non-target seabird species on the island, as many are not resident on the island during the winter months.

Currently, the eradication exercise is planned for the austral winter of 2023 and, to review and update the Project and Operational Plans, a Project Manager (Dr Anton Wolfaardt – photo left) and an Operations Manager (Mr Keith Springer – photo right) have been appointed.

A project of this nature requires substantial funding. To date, funds provided and committed are comprised largely of donations, government funding and crowd sourcing to save Marion Island’s seabirds. For more information and the latest updates on the MFM Project, as well as to ‘Sponsor a Hectare’ (which is currently standing at just over R2 million), please visit http://www.mousefreemarion.org.za

A project of this nature requires substantial funding. To date, funds provided and committed are comprised largely of donations, government funding and crowd sourcing to save Marion Island’s seabirds. For more information and the latest updates on the MFM Project, as well as to ‘Sponsor a Hectare’ (which is currently standing at just over R2 million), please visit http://www.mousefreemarion.org.za

Text compiled by Carol Jacobs - Directorate: Biosecurity (DFFE) Images from Marion Mouse Free Project, Stefan Schoombie, FitzPatrick Institute and Antarctic Legacy of South Africa digital archive. Cover Image: Otto Whitehead

,

“Marion Island is the jewel in South Africa’s island crown – it is huge and beautiful, hosts an astonishing array of endemic species and charismatic marine megafauna, and is pristine. Or nearly pristine.

“Marion Island is the jewel in South Africa’s island crown – it is huge and beautiful, hosts an astonishing array of endemic species and charismatic marine megafauna, and is pristine. Or nearly pristine. The Mouse-Free Marion project is gaining increasing momentum, as we work towards an eradication operation in the austral winter of 2023. The Mouse-Free Marion Project, a collaborative project underway to eradicate rodents from Marion Island, currently has the following opportunities available:

The Mouse-Free Marion project is gaining increasing momentum, as we work towards an eradication operation in the austral winter of 2023. The Mouse-Free Marion Project, a collaborative project underway to eradicate rodents from Marion Island, currently has the following opportunities available:

I grew up in

I grew up in

I continued pursuing an MSc and PhD in the biogeography of birds and plants in Africa: somewhat warmer and greener places (I completed these degrees in Stellenbosch and in Denmark respectively). Here I developed my second passion: savanna ecology. After taking up my position in the

I continued pursuing an MSc and PhD in the biogeography of birds and plants in Africa: somewhat warmer and greener places (I completed these degrees in Stellenbosch and in Denmark respectively). Here I developed my second passion: savanna ecology. After taking up my position in the

Much of the work that we have been doing on Marion Island deals with invasive species (especially plants) and what determines their distribution and success. Even though sub-Antarctic islands like Marion Island are some of the most isolated places on Earth, they have not been totally spared from human activities. Invasive species constitute one of the largest threats to the islands. These have mostly been introduced accidentally in e.g. building rubble, stuck in people’s shoes or the Velcro of their jackets, or in food supplies. Not all exotic species that have arrived at the islands have survived, but those that have, have often managed to spread and in some cases have had large negative impacts on the native species and ecosystem. Additionally, Marion Island is rapidly warming, and this is benefitting invasive species which are able to better survive under the mild conditions. How invasive species will be affected by climate change compared to native species forms a further particular interest. There is already some evidence of invasive species benefitting more than native species; but together with Prof Michael Cramer from UCT and Brad Ripley from Rhodes University, we are also studying how factors other than climate, e.g. soil characteristics, may limit the spread of invasive species, even under climate change. (image below during The POLAR2018 symposium in Davos, Siwtzerland)

Much of the work that we have been doing on Marion Island deals with invasive species (especially plants) and what determines their distribution and success. Even though sub-Antarctic islands like Marion Island are some of the most isolated places on Earth, they have not been totally spared from human activities. Invasive species constitute one of the largest threats to the islands. These have mostly been introduced accidentally in e.g. building rubble, stuck in people’s shoes or the Velcro of their jackets, or in food supplies. Not all exotic species that have arrived at the islands have survived, but those that have, have often managed to spread and in some cases have had large negative impacts on the native species and ecosystem. Additionally, Marion Island is rapidly warming, and this is benefitting invasive species which are able to better survive under the mild conditions. How invasive species will be affected by climate change compared to native species forms a further particular interest. There is already some evidence of invasive species benefitting more than native species; but together with Prof Michael Cramer from UCT and Brad Ripley from Rhodes University, we are also studying how factors other than climate, e.g. soil characteristics, may limit the spread of invasive species, even under climate change. (image below during The POLAR2018 symposium in Davos, Siwtzerland)

There are many things I enjoy about my career. I am always learning more, and by conducting research, I am also contributing to new knowledge. As an ecologist, I enjoy the opportunities to see wild places all over South Africa and beyond, to understand how they function, and to hopefully contribute to their protection and appropriate management. I have also met, and made friends with, many wonderful, kind and intelligent people through my work. I especially enjoy the interactions I get to have with students: it is rewarding to see them develop skills and self-confidence, and learning from them as people who possess different world views from me, have skills different to mine, and in many cases overtake me in their scientific skills and knowledge.

There are many things I enjoy about my career. I am always learning more, and by conducting research, I am also contributing to new knowledge. As an ecologist, I enjoy the opportunities to see wild places all over South Africa and beyond, to understand how they function, and to hopefully contribute to their protection and appropriate management. I have also met, and made friends with, many wonderful, kind and intelligent people through my work. I especially enjoy the interactions I get to have with students: it is rewarding to see them develop skills and self-confidence, and learning from them as people who possess different world views from me, have skills different to mine, and in many cases overtake me in their scientific skills and knowledge.